Thought LeadersDr. Linda KahnAssistant Professor, Environmental PediatricsNew York University Grossman School of Medicine

Thought LeadersDr. Linda KahnAssistant Professor, Environmental PediatricsNew York University Grossman School of Medicine

With PFAS being commonly found in households worldwide, what are the health and economic impacts of these forever chemicals? In this interview, we speak to Dr. Linda Kahn to find out more!

Please could you introduce yourself and tell us what inspired your latest research?

I am an Assistant Professor in the Division of Environmental Pediatrics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. Among other things, my research focuses on the health effects of environmental chemicals that we're commonly exposed to in our everyday life.

While it's all very well and good to advise people about lifestyle changes they can make to try to avoid toxic chemical exposure, sometimes those choices are expensive, for example, purchasing only organic food, and sometimes you simply don't have a choice. For example, if your water system is contaminated.

A far more effective strategy from a public health point of view is to regulate the chemicals at their source, so they don't make it into our food and water, our personal and household care products, and the built environment in the first place. But industries fight this kind of regulation, and governments worry about the costs politically as well as economically.

We thought it might help to persuade policymakers to take action if we presented them with the healthcare and loss of productivity costs of inaction, which it turns out are very high indeed - and we just focused on one class of chemicals!

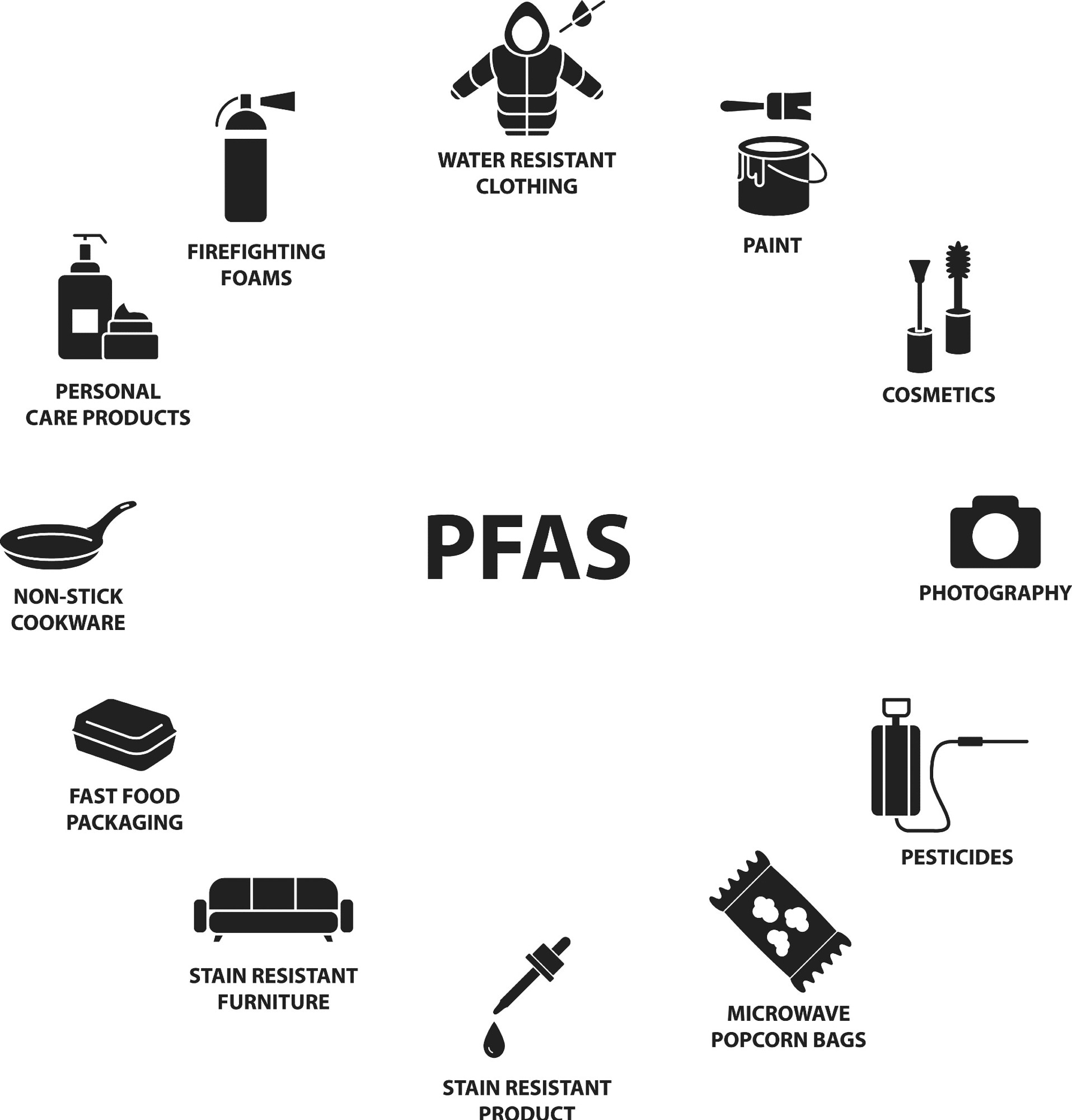

Image Credit: Vector street/Shutterstock.com

In your latest research, you looked into the economic costs of 'forever chemicals'. What is meant by the term 'forever chemicals', and where are these chemicals commonly found?

The chemicals we focused on—per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—are known as "forever chemicals" because they break down very slowly in the environment. And once they get into your body, they can take years to eliminate, meaning they have lots of time to cause harm.

PFAS have been around since the 1930s when it was discovered that they could be used to provide nonstick and waterproof coatings on surfaces. Eventually, they were incorporated into all kinds of consumer products, including nonstick cookware, the linings of microwaveable popcorn bags, the linings of food containers (do you ever wonder why the grease from a pizza doesn't seep through the cardboard box?), stain-resistant fabrics and carpets; they've also been found in chain lube, dental floss, and even some cosmetics.

At the same time, certain members of the PFAS family were found to have firefighting potential and became prevalent in firefighting foams used at airports and military bases. For this reason, communities near factories that produce these consumer products (e.g., Teflon) and communities near airports and military bases often have water supplies contaminated with PFAS. Even if we don't live in these areas, almost all of us have detectable PFAS levels in our blood.

Despite these chemicals being commonly used in household items, they can lead to detrimental health problems later in life. What are some of the health problems associated with daily exposure to these chemicals?

PFAS can mess with your hormones—your endocrine system—which controls thyroid function, reproduction, and metabolism. So many health effects that have been shown to be associated with PFAS exposure are in these areas: increases in obesity, diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, infertility, low birth weight, testicular cancer, breast cancer, hypothyroidism, and thyroid cancer. In addition, PFAS exposure can suppress your immune system, making vaccines less effective.

Can you tell us more about your latest study, including how it was conducted and what you discovered?

Using nationally representative data on PFAS exposure in the United States, US Census data on the populations affected by each disease (for example, women of reproductive age for polycystic ovarian syndrome), and the strength of the association of PFAS with each health outcome, we calculated what percent of cases of each disease that occur each year could be attributed to PFAS. We then calculated the cost of each case, both direct (healthcare expenses) and indirect (lost productivity), and multiplied that by the number of attributable cases to get a cost per year for each disease.

When we summed up the cost for the diseases with the strongest evidence for association with PFAS exposure, we got a conservative estimate of $5.52 billion per year; when we also factored in health outcomes for which we think associations are likely but there still needs to be more research, the estimate rose to $62.6 billion per year.

Image Credit: Gegambar/Shutterstock.com

If the presence of these chemicals was reduced across households, what impact would this have not only on the health of individuals but the economy also?

The effect of disease can't be measured only in dollars in cents. Most importantly, people would be healthier and lead happier, more productive lives. In the US, where we don't have national health insurance, illness is a huge source of stress and financial strain for individuals.

On top of that, we have costs to the government, which also pays the price when people become ill, for example, if they receive public insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) and provides remediation for children with disabilities because they were born too small. The cost to the economy is also huge, as people are less productive when they are ill or have to take care of sick family members.

Despite your study results and other supporting evidence, these chemicals are still commonly distributed worldwide. What more should governments, policymakers, and organizations be doing to raise awareness surrounding PFAS and their associated health problems?

Translating the results of scientific research into the adverse health effects of PFAS into language that policymakers and the general public understand is essential. I think the word about PFAS is finally getting out, certainly in areas where water contamination has occurred, and citizens are becoming more vocal in demanding that politicians and industry take action.

But in the US in particular, money talks, so demonstrating the enormous costs of inaction can be particularly effective in getting the attention of policymakers who may up until now have balked at the price of remediation.

Image Credit: Irina Kozorog/Shutterstock.com

The Environmental Protection Agency has also recently decided to lower the safe allowable limit of these chemicals in water. How important was this decision, and what implications will it have for US citizens?

It is important, but only if it is enforced. Many of us believe that even this new limit is too high and that we must go even lower. One of the paradoxical things about endocrine-disrupting chemicals is that they often have negative effects at very low doses, and there may not be any truly "safe" limit.

What are the next steps for you and your research?

My colleagues and I will continue to conduct studies to add to the evidence base around the health effects of PFAS and other environmental chemicals and to try to communicate our findings in such a way that they can effect positive change in people's lives.

Where can readers find more information?

- https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects/us-population.html

- https://www.epa.gov/pfas

- https://www.ewg.org/areas-focus/toxic-chemicals/pfas-chemicals

- https://www.ewg.org/interactive-maps/pfas_contamination/

- https://silentspring.org/project/pfas-reach

About Dr. Linda Kahn

Linda G. Kahn, PhD, MPH, is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Population Health at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, where she applies a life course approach to reproductive epidemiology. Her research interests span three interrelated areas: 1) the role of preconception and prenatal environmental exposures in pregnancy and postpartum health, 2) predictors of male and female reproductive development and fertility, and 3) health outcomes of assisted reproduction in both women and children.

Dr. Kahn received her MPH in Population and Family Health and her PhD in Epidemiology from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. Prior to her career in public health, she spent two decades as a book editor and collaborator specializing in women’s studies, psychology, health, maternity, and childcare.

User Center

User Center My Training Class

My Training Class Feedback

Feedback

Comments

Something to say?

Log in or Sign up for free