On a beach in the Caribbean, a nonprofit called Project Vesta will soon begin testing a radical new way to fight climate change that involves spreading ground-up olivine—a cheap green mineral—over the sand, where ocean waves will break down the mineral, which in turn will pull CO2 from the air. “Our vision is to help reverse climate change by turning a trillion tons of carbon dioxide into rock,” says Tom Green, executive director of Project Vesta.

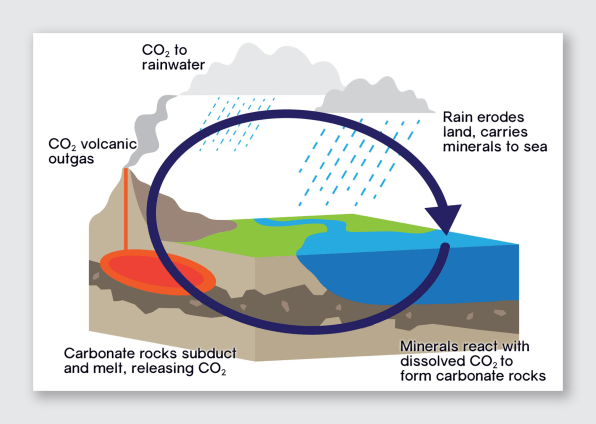

The idea is to speed up a natural process that normally takes place very slowly, over geological time. “When rain falls on volcanic rocks, those rocks dissolve a little bit, and it triggers a chemical reaction that pulls carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and into the water as a molecule called bicarbonate,” Green says. Grinding up olivine, and then spreading it on beaches where ocean waves can further break it down, triggers the same chemical reaction that pulls CO2 out of the air. In the water, marine organisms use the bicarbonate to build shells, and it will eventually end up as limestone on the floor of the ocean.

Past studies have theorized that the process works, but until now, no one has attempted to actually do it on beaches. “About 30 years of scientific research has gone into this, including a lot of theoretical work, a lot of lab experiments,” Green says. “Where we came along was to say, why is this stuck in the lab? We need real-life beach experiments to prove that this actually works in the wild . . . We exist to cross that chasm between the world of academia, which was doing a lot of theoretical experiments, and ultimately, the government and privately funded rollout.”

The nonprofit came out of a think tank called Climitigation that worked to identify solutions for climate change that had large-scale potential but little investment so far. “This particular technology was the one that really bubbled to the top of the list as having really a lot of potential to help reverse climate change, and having had relatively little investments that have gone into it,” he says. Project Vesta now has one early funder: Stripe, the credit card processing company, which pledged last year to begin spending $1 million a year on “negative emissions,” or carbon removal technologies. The nonprofit is now working to raise another $1.5 million for its early experiments.

If it finds proof that the process works, Project Vesta plans to share open-source instructions to replicate. Done at scale on beaches and in the shallow water on continental shelves, it could make a major difference. “If we spread olivine over 2% of the world’s shelf sea, then that will be enough to capture 100% of human emissions,” Green says.

User Center

User Center My Training Class

My Training Class Feedback

Feedback

Comments

Something to say?

Log in or Sign up for free