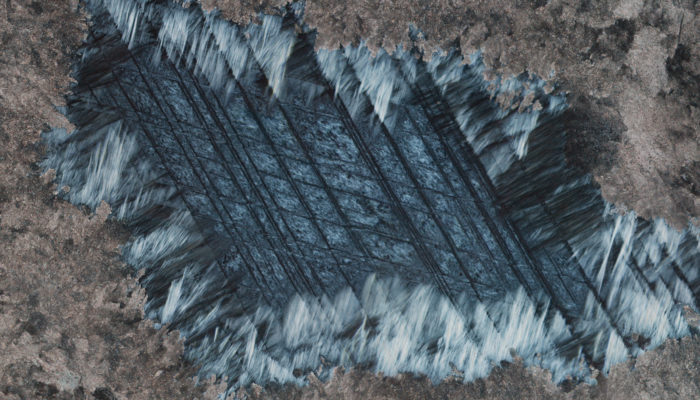

The structures in this photo might look three-dimensional, but they are completely flat. It is a photo of a polished thinsection of a rock, taken through a petrographic microscope under cross-polarized light. The width of the image is just 2 mm. The brownish mineral around the edges is carbonate, the white to grey mineral in the centre is serpentine, a water-bearing silicate mineral. The different shades of grey are due to different orientations of the crystals in this sample.

When I first saw the structure in the photo, I was amazed. The mineral in the centre is clearly serpentine. However, the overall shape with the straight, parallel lines outlining perfect rhombs looks exactly like that of a large, ideal carbonate grain with its typical parallel twins. How is this possible?

Let us first look at what is happening in these rocks in general. The structure shown in the photo is just a tiny part of one little sample from the Feragen Ultramafic Body, close to the town of Røros in central Norway. This area is known for a unique rock type called ophicarbonate, which is a carbonated ultramafic rock. The carbonation of ultramafic rocks is important for the global carbon cycle and has recently received much attention because this reaction involves the sequestration of CO2 into solid rock.

The ultramafic rocks in this area were first hydrated to serpentinites. Later, the serpentinites were fractured. Through the fractures, carbonate-bearing fluids came into the rocks and reacted with them. Carbonate minerals both filled the fractures and replaced parts of the rock fragments. While these processes involved many details that were interesting for us, they were more or less what we expected to find. However, what we see in the image above is exactly the opposite: Instead of carbonate replacing serpentine, serpentine is replacing carbonate! This was surprising, but seems like the only explanation for the development of this structure. A large carbonate grain grew in a fracture between some serpentinite fragments. Later, when fluid conditions changed, this carbonate grain was dissolved and serpentine grew again. To preserve the minute microstructures of the carbonate grain, dissolution and precipitation must have been closely coupled in space and time. As soon as a the first bit of carbonate was dissolved, serpentine precipitated in its place. These rocks obviously had a more complicated history than we thought. Fluid conditions varied, determined either by two separate events or by an ongoing reaction that moved through the rock and led to a continuous change in fluid composition.

Another problem is the occurrence of all the fine-grained carbonate surrounding the serpentine. How did that form? Was there yet another carbonation event? In that case: Why did our beautiful serpentine in the middle survive that? I have long concluded the project this was part of, but am still puzzled by this structure. Things are always more complicated than we expect.

(More information on the context of this image can be found in this recent article: Dunkel, K. G., Jamtveit, B.& Austrheim, H. (2019). Ophicarbonates of the Feragen Ultramafic Body, central Norway. Norwegian Journal of Geology 99, 1-18.)

Photo and description by Kristina G Dunkel

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.

User Center

User Center My Training Class

My Training Class Feedback

Feedback

Comments

Something to say?

Log in or Sign up for free